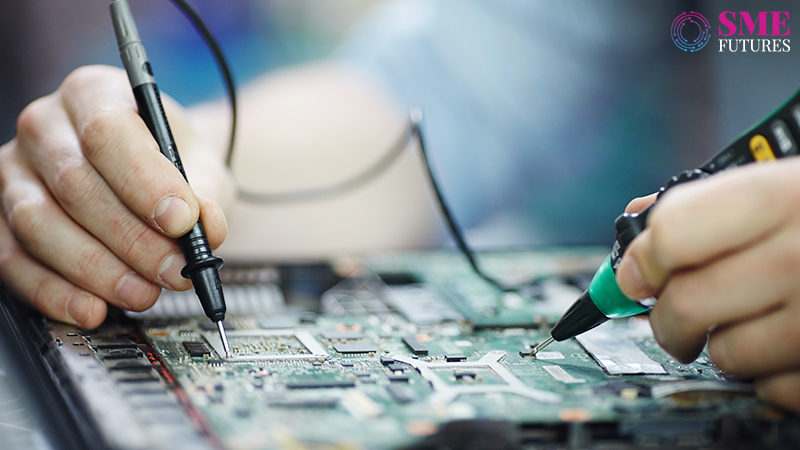

If any sector in India has changed dramatically over the last two decades, it is the electronics industry. Everything about it has changed, from its technologies to its electronic products to how people consume them. The tectonic shift towards the adoption of electronic gadgets in daily life has changed our lifestyles and resulted in an insatiable appetite for electronic device consumption. This implies that consumption would be directly proportional to population, and India, as in the past, would continue to be a major consumer of electronic goods.

However, India’s capacity for electronic manufacturing is still far from par.

To give you an idea, in 2012-13, India’s share in electronics production at the global level was 1.3 per cent. As of now, it has only gone up to 3.6 per cent in 2019. Whereas so far China ranks number one.

“China has always held the centre stage when it comes to manufacturing, especially in the realm of electronics. The country produces 70-80 per cent of the raw materials required by the appliances industry such as semiconductors and panels,”

tells us Avneet Singh Marwah, CEO, Super Plastronics, and India licensee of European consumer electronics brand THOMSON.

Meanwhile, another fact is that at large the country still relies on imported electronic goods, so much so that next to oil, it is electronics that are our most imported commodity.

India is already witnessing a rapid rise in its digital quotient, which may lead to the import of electronics exceeding that of oil.

But that’s not what the nation wants. Instead, the government wants to bring down electrical imports, more precisely it wants to decrease our dependence for electronics goods on other regions.

With that aim in mind, in 2019 the Indian government come up with the National Policy on Electronics (NPE) to position India as a global hub for Electronics System Design and Manufacturing (ESDM). The NPE has been further divided into four schemes, and its overall intent is of manufacturing $400 billion (approximately Rs 26,00,000 crore) worth of electronics by 2025.

Considering it as a ‘better late than never’ move, the introduction of the NPE was perfectly timed. There was already an air of realisation about becoming self-reliant, and the focus had shifted towards local manufacturing. The COVID-19 outbreak just added fuel to this idea.

But expecting overnight results is extremely unrealistic. And that too at a time when India’s manufacturing capacity came to an almost complete halt due to the impact of the pandemic. For instance, localised lockdowns and raw material shortages including semiconductor and manpower shortages have significantly impacted the manufacturing of mobile handsets. Given the uncertainties, IDC statistics show that there was a decline of 14 per cent in smartphone shipments for the January-March 2021 period. Which implies that there will definitely be delays in meeting the targets set by the NPE.

Furthermore, the manufacturing sector of India doesn’t seem to be doing so well at the moment.

According to IHS Markit data, there has been a slight fall in the growth of the manufacturing sector in August. The Manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Index fell from July’s three-month high of 55.3 to 52.3 in August.

There are mixed opinions on whether India can achieve such an ambitious target in four years considering the many obstacles that it has to contend with in these fraught times.

The current situation

Over the years, with the evolution of the digital economy, it has become clear that the ESDM industry is substantial for India. In the government’s view, electronics manufacturing is estimated to register an annual growth rate of 30 per cent over the next five years and clock Rs 11.5 lakh crores worth of additional production during this period.

That’s why there is a lot of focus on this sector. The Make in India, Self-reliant India, Digital India and Start-up India programmes are prioritising electronics hardware manufacturing.

Meanwhile, the big brands and a variety of other brands like Vingajoy and Crossbeats are witnessing ease of doing business due to the numerous opportunities being made available to them. Archit Agarwal, the co-founder of Crossbeats, a consumer tech company comments, “Lately, we have been witnessing significant changes in the electronics manufacturing policies and its business conditions. The latest initiatives like ‘Make in India’ have created a demand for home grown brands to step up and bolster domestic manufacturing.”

Secondly, the ever-increasing demand for electronics in the last few years has also given the sector a great push towards growth.

“The present scenario in the Indian electronics sector has witnessed a significant boom in demand which can be attributed to several factors such as the increase in demand from households, the changing lifestyles of individuals, easier access to credit, and rising disposable incomes,”

says Lalit Arora, Co-founder of VingaJoy, a New Delhi based consumer electronics and gadget accessory brand.

In a nutshell, to meet this rising demand, the electronics manufacturing industry is working towards self-dependency, while promoting and encouraging Made in India products. Thereby curtailing the imports from other countries, he adds.

Not only this, the ESDM sector has a broad spectrum. To put it simply, it has a participation in each and every sector in one way or another. Concurring with the same, Arora comments, “Yes, the sector is also providing structured incentives to support the manufacturing of core electronic components and the production of consumer electronics which include gadgets such as home theatres, smart LED TVs, speakers, headphones, etc. thus increasing affordability due to price reductions, income growth, ease in financing and the mandatory digitisation of the broadcast sector.”

However, the pandemic has certainly shaken up this industry.

For starters, the crisis has exposed the critical issue of our overdependence for products on one single market. At the same time, it has saddled the manufacturers with various challenges since the supply chain broke.

Elaborating on the same, Marwah tells us that due to an increase of more than 300 per cent in the need for these raw materials for the various categories of electronics, manufacturers are seeing a drastic price increase in the consumer electronics sector.

Another pressing issue that the manufacturers had to deal with was that of shortages within the semiconductor industry. Which hit the production volumes of the auto makers drastically.

According to Indian car maker Maruti Suzuki’s Chairman RC Bhargava, the issue is temporary and is expected to be over by 2022. But mostly, it’s a wait and watch situation.

Then there are other issues which need to be worked on.

“We need a skilled labour force that will be led by sophisticated production units’ technologies which need to be invested in by the government,” asserts Marwah.

Cashing in on the opportunity

Lately, the global players have started to look beyond China.

This trend was born partly due to the US-China trade war, the surging labour costs and the supply chain disruptions engendered by the pandemic. In fact, research firm Gartner revealed that a third of the supply chain leaders had plans to move out of China by 2022-23. The government recently stated that out of these, four ESDM players have already diversified their manufacturing bases in India.

Which the experts believe is a golden opportunity for collaboration.

Despite the challenges, Indian manufacturers are optimistic and upbeat about how the global ESDM firms are considering India as their tentative shop floor.

“Everyone has felt the brunt of China’s monopoly and the stage is ready for more countries to step in and challenge that,” says Marwah. According to him, India as a competitor will also ensure better price controls and bigger investments in our country.

“The ODM and OEM businesses will be coming through electronics and due to this positive momentum, the government must continue to fully capitalise on it. With this, we can also see the international players announcing the setting-up of assembly lines and manufacturing stations within the bounds of the country. Along with that, the leadership must take decisive steps to be able to take full advantage of this sentiment that is also echoing at a global level,” he further elaborates.

Whereas according to Agarwal, going local is all about aligning with the government’s aim to achieve growth. “Promoting home grown brands and incentivising them to set up and run manufacturing units in the country will strongly complement the government’s initiatives such as the ‘Digital India’ and ‘Make in India’ campaigns,” he says.

Although during the pandemic, the realisation of the importance of and the efforts towards self-reliance grew, there is still a long way to go. “However, we now need to add real value to the existing ecosystem and bring in new players if we want to see a continuous growth in these figures. Currently, all electronics brands are required to assemble their products in India. However, until we don’t have a manufacturing setup in place such sincere efforts will become redundant soon,” suggests Marwah, adding that it is going to take time.

Meanwhile, the question remains about whether the goals for 2025 are going to be met within the given timeframe. Are we anywhere near to achieving the ambitious targets of the NPE?

Can India Inc. achieve it?

Although 70 per cent of the market’s demand is met through imports, the stakeholders are highly optimistic about creating a $400-billion electronic manufacturing ecosystem by 2025.

This also includes the production of 1.0 billion mobile handsets by 2025, valued at $190 billion, including 600 million mobile handsets valued at $ 110 billion for export.

In Marwah’s opinion it is a realistic target. “India has the talent, capability and capacity to achieve this target. We have time and again showcased our innovative capabilities by creating new age and innovative software,” he comments.

Crossbeats’ Agarwal expresses similar sentiments, saying, “Expecting a 6x spike in the domestic electronics market by 2025, the race against time for the economy is pretty rapid and we can expect to see numbers like $70 billion to $400 billion as achievable targets.”

According to him, Indian electronic manufacturers such as him are positive that they will be able to achieve this target in the next 4 to 5 years, “If the government supports small or mid ranged businesses by creating more opportunities,” he avers.

Undoubtedly, the high optimism is on account of the rise in digital transformation, the demand for ICT hardware and the need to connect digitally. However, the achievement of this target also depends upon the course of the scheme as it is expected to contribute towards the realisation of a $1 trillion digital economy.

On this Arora of Vingajoy says, “Having initiated the research and development and the technology upgradation, making infrastructural changes is also required and we are pulling out all the stops to ensure that we achieve this target and reach the $400 billion mark.”

Marwah says that this has set a precedent and is an example of the fact that our country is more than ready to accommodate raw material production investments; however, the real value addition will have to come from the leadership, to begin with. “In recent times we have seen announcements by major brands about them setting up shop and screen manufacturing bases in India. This will change the landscape and level the playing field alongside ending monopolies and ensuring price reductions for all players globally,” he said.

Mobile handset industry to shoulder the responsibility

It is a fact that at least 95 per cent of mobile phones are assembled, and they account for about 27 per cent of the electronic products industry in India. India Inc. is betting big on the mobile handset industry to achieve the objectives of the NPE.

“The plan is to transform India into the world’s biggest export hub for mobiles after China,” elaborates Arora. “The industry is banking upon one segment of mobile devices, which it hopes will contribute half the production value of electronics,” he said.

Mobile phones account for about $26 billion of the electronics industry in India and represent the largest market segment in it. With the impending transition to 5G technology and novel tech such as IoT, an estimated 25 billion ‘things’ would be connected via phone devices by 2025. This will exacerbate smartphone consumption even more. For India, this consumption can grow by 1.1 billion by 2025 from its current level of half a billion. Which implies the need for large mobile shipment imports. That’s another reason to domesticate mobile manufacturing- to reduce the need for large imports.

At the same time, for India this is a window of opportunity to become the hub for the manufacturing and export of mobile devices, where its share is fairly low at the moment.

“Promoting home grown brands and incentivising them to set up and run manufacturing units in the country will strongly complement the government’s initiatives such as the ‘Digital India’ and ‘Make in India’ campaigns,” comments Agarwal.

At present, China (including Hong Kong) and Vietnam are the leaders in the global mobile handset manufacturing space, which is dominated by 5 companies—Samsung, Apple, Huawei, Oppo and Vivo. These two countries act as their global value chain (GVC) and supply 80-85 per cent of the components.

Also, China (61 per cent) and Vietnam (11 per cent) together account for about 72 per cent of the global mobile phone exports.

“Our existing software capabilities coupled with an enhanced manufacturing setup will allow our players to do backward integration, develop new technologies and also cut costs since there will be an alternative to China dictating raw material prices,” says Marwah.

Also, the government’s move to ban imports of Completely Built Unit (CBUs) for large appliances was seen in a positive light. It is also being interpreted as a positive step by the government which is serious about challenging the existing manufacturing powers by investing in and adding value to the ecosystem that exists now and is also aiding the new investors who see potential in investing in India.

What’s delaying the achievement of the NPE goals

Industry players and brands are recognising the vigour with which the Government of India is pushing the policy of make in India, opine the experts. However, it still has a long way to go given that the industries have their own issues to handle post the lockdowns.

For instance, the customer purchase journey is not the same as it was during pre-COVID times and it’s still evolving post the lockdowns.

Agarwal says, “Manufacturers need to embrace the best digital practices, while also adapting to the changing supply chain requirements. Due to this shift, there have been massive shortages of raw materials, labour, and other chip accessories.”

Marwah also adds in, “We did see a negative impact during the second wave since each state made their own guidelines for the lockdowns. This made our distribution schedules very erratic and hampered our supply chains. Day to day e-commerce functioning was disturbed. Some states allowed for TVs to be delivered to customers while the rest only allowed for very basic essentials to be transacted upon.”

Furthermore, the experts feel that the ESDM industry is also grappling with a skill gap.

“It impacts the quantity and quality of skilled workers, particularly in positions requiring more than a high school diploma, but less than a four-year college degree. It’s also notable that a large portion of the electronics assembly is still being done by hand and outfitting factory workers in the appropriate PPEs is impacting costs and is slowing down the lines as you have less people,” explains Agarwal.

While, according to Arora, some of the major challenges that the domestic manufacturers are facing today post the lockdowns include competition from cheap imports and a lack of cutting-edge tech with their effective costs being higher than their competitors. Besides that, the NPE also does not address the core challenges faced by the sunrise industry manufacturers.

More support is required besides the policy

The policy is there, but the manufacturers are being increasingly vocal about the need for more promotions, domestic trade and building facilitative programs. Which in turn will help transform India into a key destination for electronics manufacturing and strengthen its exports sector.

The Electronic Industries Association of India (ELCINA) recommends incentivising capital investment as a support mechanism.

According to them, the ESDM industry is suffering from an 8-10 per cent disadvantage in comparison to its international counterparts. To address this, the industry requires a scheme for the PCBA/EMS sector that provides a 25 per cent capex subsidy. Electronic components have already reaped similar benefits. This will also allow MSME’s to invest in this industry.

Manufactures are also demanding the setting up of domestic testing facilities.

Given that they face stiff global competition, the lack of testing and certification facilities in the country are holding them back. This is especially true for when Indian manufacturers attempt to export their products to developed markets that have stringent quality approval requirements.

These facilities do not exist in India and obtaining certifications from outside sources is prohibitively expensive.

Another recommendation is that non-ITA classified Printed Circuit Board assemblies should be subject to customs duty (PCBAs). According to the stakeholders, PCBAs are a huge opportunity for the electronics manufacturing sector. When imposed, a customs duty of 10-20 per cent can attract investment in this sub-sector. According to ELCINA, the PCBA sector could increase from $23.5 billion to $152 billion over the next five years.

Experts such as Marwah feel that the TV manufacturing sector should also be covered under the PLI scheme, as it’s the large appliance which has the highest penetration in the market as compared to the others. Another reason is that it can attract JVs with global brands, especially the Chinese ones.

Commenting on it he says, “The television production sector must come under the government’s PLI scheme. We will soon be the 3rd largest TV market, and this will ensure that the Indian brands are able to fully capitalise on this potential. The GST rate on TVs is also of grave concern. This restricts us from competing with similar TV brands on a global stage who do not have such high tax percentages imposed on them.”

Suggesting some other measures, Arora recommends that the government can make some additions in the NPE to facilitate the ease of doing business. “In my opinion, measures such as maximizing incentives, availability of subsidised lands, special grants if possible, along with speedy approvals on project plans, a one window clearance for grants and licenses and a relaxation in taxes till the break-even period will add more value to the policy. In turn they will support us immensely,” he explains.

Agarwal also weighs in. According to him, creating specialised governance structures to cater to the specific needs of the electronics manufacturing sector is what the sector needs. “Fast-paced technological innovations in the business modules can also contribute to the rapid growth of home-grown businesses in shorter time spans,” he suggests.

At the same time, R&D and design are also critical for sustained growth and maintaining a competitive edge for the industry. ELCINA urges that R&D should be incentivized by allowing CSR funds to be channelled for research, innovation and for supporting start-ups.

“We have repeatedly advocated for the above effective measures that can be taken up by our leadership. The GoI has started a lot of schemes but to ensure that the full benefits come out of them, there needs to be some mechanism. It should also ensure that the regulations are in sync with the current times and needs while also acknowledging the shortcomings that still remain,” says Marwah.

Navigating forward

After the 1980s Doi Moi Reforms, Vietnam pivoted in the electronics manufacturing sector. Over the years, this nation has positioned itself as the 4th largest exporter of electrical goods and components to the US. Learning from Vietnam, India could also work on the obstacles that are hampering its ESDM sector.

Meanwhile, initiatives such as the Phased Manufacturing Programme (PMP) or the NPE in general have been able to attract huge investments by foreign investors in India’s electronics industry.

However, the pandemic has proved to be a dampener. But it has also forced the industry to change its old ways.

“After many disruptions, it has made us better prepared to handle future crises,” says Marwah. This has also reinstated the investors’ faith in the system, and we can expect $ 30 billion worth of investments coming in provided that the government also works upon adding value to the current ecosystem with regard to the production of raw materials.

The stakeholders are optimistically forecasting a growth in the business of the sub-sectors of the ESDM industry—semiconductors, panels, screens, washing machines, refrigerators, LED lighting and cellular phones too. What the government can do to fast track this process is that it should make sure that it has the relevant long-term policies along with the proper regulatory mechanisms in place. All this will go a long way in ensuring India’s place on the global stage.