In the narrow lanes of the Hindu pilgrimage city of Varanasi, the centre of a famed silk-weaving industry, there’s little sign of the nascent economic recovery trumpeted by India’s policymakers.

Sales of the heavily brocaded silk sarees made in the ancient city on the river Ganges are currently down 70 per cent from the pre-pandemic period, locals say. Many weavers have shut down their looms, others have sold them, and some workers have pulled their children out of school, unable to afford the fees. “Prices are sky-rocketing and I am unable to get even one-third of what I used to earn before the pandemic,” said Mohammad Kasim, a weaver who has sold two of his 16 looms.

A surge in global prices of petrol, diesel, cooking gas and other commodities like steel and copper is hurting millions of Indian households and businesses, already affected by the pandemic.

India meets 80 per cent of its oil needs through imports, and the government imposes more than 100 per cent tax on fuel products like petrol and diesel. Consumers and businesses end up shelling out higher fuel and transport rates compared to other emerging economies.

In addition to this, the fall in consumer incomes after the outbreak of the pandemic early last year are threatening demand for price-elastic goods.

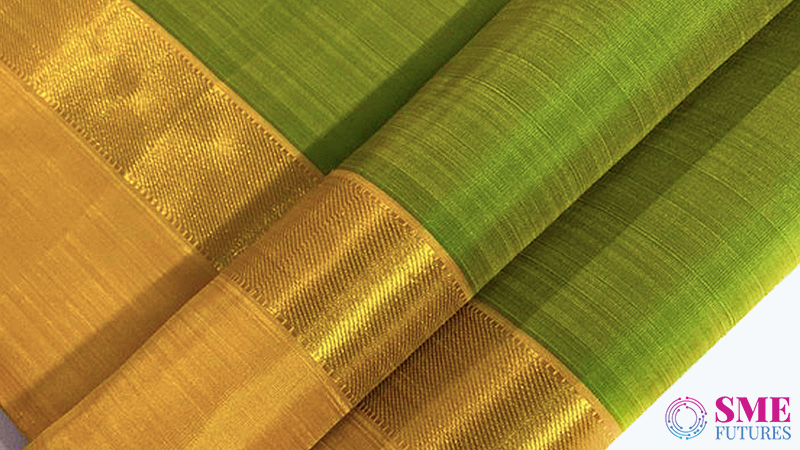

Brocaded with gold, silver and copper, the heavy Banarasi silk sarees made in Varanasi, which is also called Benaras, are sold across India and overseas for women to wear at weddings and special occasions.

Weavers say they are struggling with shrinking demand as the expensive sarees they make are substituted with cheaper varieties, as well as the high prices of raw silk and brocade.

Prices of raw silk have gone up to 4,500 rupees ($61) a kg from 3,500 rupees in the last four months, Kasim said, while brocade material like copper and silver has become costlier by 40 per cent – leaving profit margins in saree making to below 10 per cent.

Kasim is among millions of Indians in small manufacturing and services – which account for 90 per cent of jobs – who are complaining of a double whammy of high prices and weak demand. Retail inflation has breached the central bank’s upper limit of 6 per cent year-on-year a couple of times this year although in August it eased to 5.3 per cent.

That poses a risk to the nascent recovery in Asia’s third largest economy after the worst-ever contraction of 7.3 per cent in the last fiscal year ending in March.

The economy grew an annual 20.1 per cent in the April-June quarter, and the government’s chief economic adviser, K.V. Subramanian, said: “India is poised for stronger growth”.

But N.R. Bhanumurthy, vice-chancellor of Bengaluru Ambedkar School of Economics University, said inflationary pressures pushed up by global supply chain issues and sluggish domestic demand would likely have a long-term impact on Indian manufacturing. “With the rising risk of high inflation in the short term and massive unemployment in recent past, I don’t see prospects of a complete recovery soon,” he said.

No consumer demand

Wholesale price-based inflation, a proxy of producers’ prices, rose in double-digits for the fifth month in a row to 11.4 per cent in August year-on-year, stoking concerns companies could pass on rising costs to consumers.

Unlike some advanced economies, where governments have offered massive stimulus packages, India’s pandemic relief focused on credit guarantees on bank loans and free food grain to poor.

Rajan Behal, general secretary of the Varanasi cloth merchants’ association, a body of about 800 wholesale traders, said most businesses were reluctant to take on new bank loans even though the government has promised to stand guarantee. “We would have happily mortgaged our properties for loans if there was consumer demand,” he told Reuters.

The hand-loom and power loom saree manufacturing industry, employing 1.5 million people in Varanasi and surrounding towns with an annual business of 700 billion rupees a year, is facing an “undeclared crisis,” he said.

Mohammad Siraj, 45, a power loom worker, said his family was surviving on free foodgrains – offered by the federal government to two-thirds of the 1.3 billion population as pandemic relief. Still household costs were high. “I have taken my daughters out of school because I cannot afford the fees anymore,” Siraj said.

Traders in Varanasi, which is also a major Hindu pilgrimage destination, are now praying for a pick-up in tourist inflows and garment demand during the festival and marriage season starting this month. “We are dipping into our life savings or taking on debt to survive,” said Rahul Mehta, president of the local Tourism Welfare Association, a trade body of about 100 establishments.

He said earnings from about 6.5 million annual tourist inflows, estimated at 50 billion rupees in 2019/20 before the pandemic, could revive to 10-15 billion rupees this fiscal year if there was no surge in virus cases.

But any projections of an increase in demand are hostage to the price rise.

“We might have survived the coronavirus but we will not able to bear the burden of rising prices and fall in demand,” Mehta said, adding if tourism inflows and demand for sarees did not revive in the festival season, thousands of saree makers and vendors would have to close shop permanently.