Trade between India and the other BCIM-EC (Bangladesh, China, India, Myanmar – Economic Cooperation) countries, like Bangladesh and Myanmar, run minimal trade balances with the country. While inward looking, navel gazing economists would say India needs to access these markets on full tilt, the foreign policy pundits would tell you that running trade deficits with economically weaker neighbours is a good measure for cementing long-term relations. China, of course, is different: it is the 800-pound Giant Panda in the room.

But, let us take a look at the figures for 2017-18: Bangladesh has exports of approximately $6.9 billion or 2.52 per cent of the total exports of India and its imports are approximately $400 million or 0.13 per cent of the total imports of India; Myanmar has exports of approximately $333 million or 0.30 per cent, while its imports are approximately $600 million or 0.21 per cent of the total Indian imports.

Considering these rather minuscule trade figures, a scope naturally exists for large expansions. But, whether traditional bilateral trade will create an environment conducive for closer cooperation on other fronts – especially security – that can be region-wide depends on how New Delhi and Beijing decides to play the “economic cooperation” game.

Let us just touch upon the security issue briefly, before we move to the familiar ground of how spreading the economic cake wide can integrate the region better. Both Bangladesh and Myanmar have terrorist groups that are inimical to the country’s interests. Plus, they belong to what is called the Golden Triangle in terms of those who track illegal psychotropic substances and its concomitant, arms smuggling.

The earlier trade route catering to these nations was the almost 1,700-kilometre-long Stilwell Road. The route of the Stilwell Road, built by the British, ran too close to Arunachal Pradesh, which the Chinese dispute as part of Tibet being its southern part. After Independence in 1947, especially after the 1962 border war with China, India realised that the road begins at Ledo in Upper Assam then comes down enters Myanmar and finally enters China’s Yunan province to Kunming, an important trading post. So, India’s strategic concerns made the road fall into disuse.

Now that the talk has veered towards opening the BCIM Corridor, the condition of the Stilwell Road is bound to crop up. But, more importantly, both India and China have an interest in developing the corridor, as it would integrate the least problematic of the South Asian region into one “common market”.

In any case, there is a rising trend in trade between the Northeastern states and Bangladesh, with Meghalaya being the largest trading partner of the seven Northeastern states and Sikkim at Rs 393.54 crore. This figure is for the period 2006 to 2008.

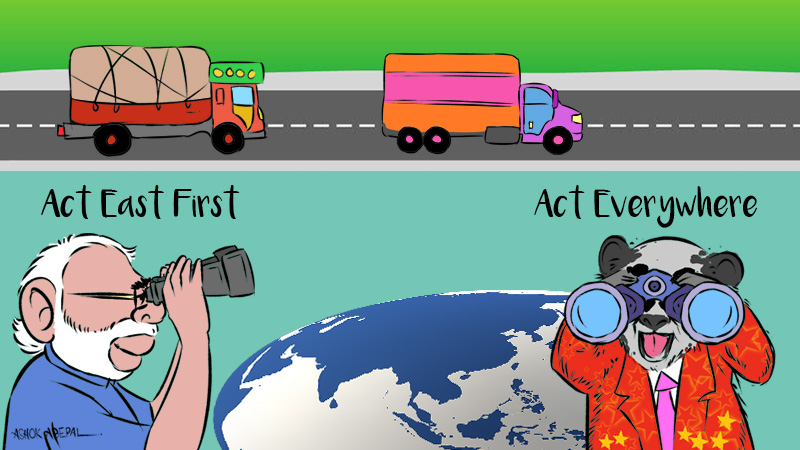

Most of the items that were exported from the region to Bangladesh and Myanmar are from the medium, small and micro enterprises (MSMEs). But, the trade figures given above are in for a quantum jump in recent years for two factors: India’s desire to take up the least difficult part of the subcontinent and connect it with the voracious Chinese market; and, two, because Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s call for “Act East, Act Fast”, a slogan that, if implemented as a policy, can potentially transform the economic and business landscape of the region. China is willing to play ball as it sees the developments a part of its Belt and Road Initiative.

The current plan for the BCIM is being handled at a Joint Working Group level of the regional body. But, last year, during the annual meeting of the multilateral organisation, China had wanted to bump it up to inter-governmental level, so that it could be discussed at a decision-making level. But, India had not played ball. New Delhi was of the view that Beijing was intending to extend its hegemony more in its neighbourhood.

While that may be true, but from a geostrategic viewpoint, a demonstrable success in extending trade with its concurrent economic development in the particularly backward region of the Northeast India could give fillip to the concept of Modi’s “Act East First”. The BCIM Corridor, beginning from Kolkata, stretches through to Jessore, Dhaka and Sylhet in Bangladesh to Mandalay in Myanmar to Kunming in China.

A recent study shows that West Bengal has the highest number of MSMEs in the country with almost 60 lakh units. The Businessworld magazine reported in January 2018: “In 2017, West Bengal also recorded the biggest bank credit flow to the MSME sector in the last five years at USD 15 billion.”

Focussing on the BCIM Corridor can fast-track trade-based economic development, with Kolkata’s hinterland being Northeast India and the West Bengal government’s policy focus being on the development of the MSME sector. The matrix that takes shape as a result can help tie the region tighter – the Giant Panda being ever present or not.